from UHDB medical museum and the Derwent Valley

by Dawn Jutton

Creating a new work necessitates curiosity. It is important to cast that curiosity wide, but that can be like trying to create a quality cloth with random strands of fraying cotton. However, what I am looking for among those complex, seemingly unrelated strands are interesting fragments to weave together and create work with context and depth to generate curiosity in the viewer.

So after a quick internet trawl my first ‘strands’ of research for this commission are images about Derby Infirmary alongside images from UHDB medical museum and information about Derwent Valley Heritage trail. This immediately led me to discover the influence of the Strutt family in the Derwent Valley during those early days of the industrial revolution in Derbyshire. As a photographer taking inspiration from heritage and landscape I needed no excuse to visit the Derwent Valley to tease out any links that might inspire some direction for my work.

As I wandered through the restored courtyards of Cromford Mills, therefore, I tried to look beyond the veneer of heritage and tourism into the distant hills for inspiration. What I found though, among the remnants of water powered innovation and dye stained walls, was an overwhelming desire to speak to the people who brought wealth to the new industrialists; to those who left their homes and families to work long hours in these huge new water-powered mills. What did the – mainly female – workers really think? Was life improved? How did it change their sense of community? What was their response to this new urge of men to mechanise and experiment with social change? Did they follow willingly – or even have an opportunity to lead- into this new world of science and social progress?

I also realised the determination to build Derbyshire Infirmary would be motivated in some part through necessity, as a response to increased accidents and health problems associated with working in confined, noisy and machine dominated spaces. Discovering Paul Elliott’s article in Medical History (2000)* set me off on a research journey to explore William Strutt’s application of architectural innovation and inventions to the original Derbyshire Infirmary – a subject he comprehensively discusses. As a member of the Derby Philosophical Society Strutt will also have recognised what Elliot describes as the ‘problems of internal hospital spatial organisation’ as discussed by the Enlightenment philosophers and philanthropists. Elliot also refers to Foucault’s description of this period as a time when ‘the medical gaze became institutionalised and inscribed in social space…’ .

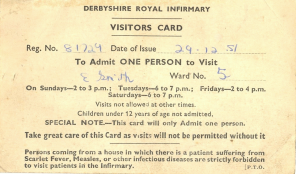

I was now busy in the back of my mind pulling together strands from Foucault’s ideas of the ‘medical gaze’ with those earlier questions about women’s lives whilst still sifting through the UHDB library’s online medical museum collection. I realise that I keep coming back to two images in the UHDB museum catalogue; an early 20th century photograph of a queue of women visitors with baskets and a Derbyshire Royal Infirmary visitor’s pass from 1951. They somehow speak to me again about the role of women; the queue of women gaze at the photographer but are anonymous, suspended in a moment of waiting. Who are they? Who are they visiting? What is in those baskets, themselves symbols of womanhood and duty. Are they simply the eggs and fruit as directed on the later visitor’s card? Are the baskets waiting to be checked by the Ward sister?

Inspired by these artefacts the still life image I’ve created weaves together the strands of my research touching on philosophy, medical history and cultural heritage. It also draws on the 17th and 18th century Dutch influenced tradition of still life painting and the dramatic candlelit science paintings of Joseph Wright of Derby, a contemporary of William Strutt. The basket and the objects spilling from it become symbolic, each carefully chosen to create a visual metaphor that attempts to foreground the medical and cultural experience of women. Background elements allude to a supposed tension between the reliance of the poor on the quack and the apothecary and the powerful new medical institutions providing care for the wealthy. Most significantly ‘The Mistaken Kindness of Friends’ will attempt to challenge the viewer to ask questions; to generate curiosity.